Part I — The Bad Investment

My name is Francis Townsend, and I’m twenty-two.

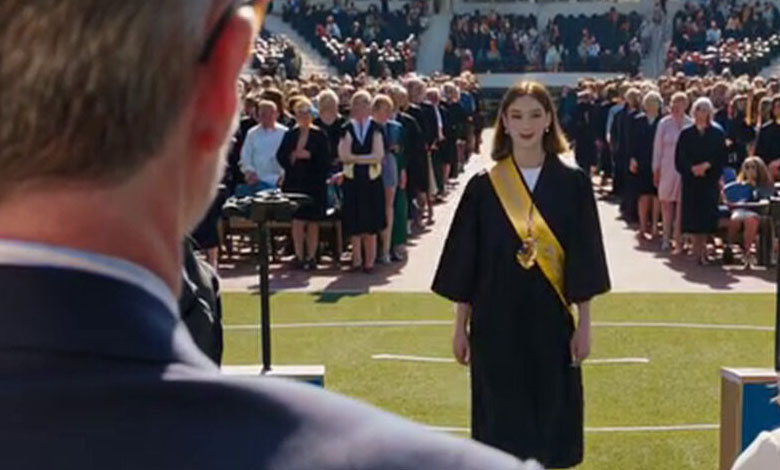

Two weeks ago, I stood on a graduation stage in front of three thousand people while my parents—the same people who once refused to pay for my education because they didn’t think I was worth the money—sat in the front row with their faces drained of color.

They hadn’t come for me.

They came to watch my twin sister graduate.

They had no idea I was even in the stadium. They certainly didn’t expect that my name would be the one called to deliver the keynote.

But this story doesn’t begin at commencement. It begins four years earlier, in my parents’ living room, the kind with immaculate furniture that never felt lived in. It begins with my father looking straight at me, in that quiet, confident tone he used when he wanted a decision to sound like a fact.

There are moments you remember the way you remember weather—heat that sticks to your skin, a storm you feel in your bones. That was one of them.

And before I take you back there, I’ll tell you this: if you’re reading from somewhere far away, if it’s late where you are or early, if you’ve ever been underestimated by the people who should have protected you, you’ll understand why I’m writing this down the way I am. Names are real. Feelings are real. The lessons—those are the most real of all.

Now: that summer evening in 2021.

The acceptance letters arrived on the same Tuesday afternoon in April.

Victoria got into Whitmore University, a prestigious private school with a price tag of $65,000 a year.

I got into Eastbrook State, a solid public university—$25,000 annually. Still expensive, but at least it lived in the realm of possibility.

That evening, Dad called a family meeting.

“We need to discuss finances,” he said, settling into his leather armchair like a CEO addressing shareholders.

Mom sat on the couch, hands folded tightly in her lap.

Victoria stood by the window, already glowing with anticipation.

I sat across from Dad, still clutching my acceptance letter, the paper creased from how many times I’d unfolded and refolded it.

“Victoria,” Dad began, “we’ll cover your full tuition at Whitmore. Room, board—everything.”

Victoria squealed. Mom smiled.

Then Dad turned to me.

“Francis,” he said, “we’ve decided not to fund your education.”

The words didn’t land right away. My brain tried to reject them like a bad translation.

“I’m sorry—what?”

He didn’t flinch.

“Victoria has leadership potential,” he said. “She networks well. She’ll make connections. It’s an investment that makes sense.”

He paused, like he was choosing the most efficient way to slice through me.

“You’re smart, Francis,” he added, “but I don’t see a return on investment with you.”

It felt like a knife sliding between my ribs—clean, deliberate.

I looked at Mom.

She wouldn’t meet my eyes.

I looked at Victoria.

She was already texting someone—probably sharing the good news—like I was just background noise.

“So… I just figure it out myself?” I asked.

Dad shrugged.

“You’re resourceful,” he said. “You’ll manage.”

That night, I didn’t cry.

I’d cried enough over the years—over missed birthdays, hand-me-down gifts, being cropped out of family photos.

Instead, I sat in my room and realized something that changed everything.

To my parents, I wasn’t their daughter in the way that mattered to them.

I was a line item. A bad bet.

What Dad didn’t know—what nobody in my family knew—was that his decision would alter the course of my life. And four years later, he’d face the consequences in front of thousands.

The thing is: it wasn’t new.

The favoritism had always been there, woven into the fabric of our family like an ugly pattern everyone pretended not to see.

When we turned sixteen, Victoria got a brand-new Honda Civic with a red bow on top.

I got her old laptop—the one with a cracked screen and a battery that lasted forty minutes.

“We can’t afford two cars,” Mom had said apologetically.

But they could afford Victoria’s ski trips. Her designer prom dress. Her summer abroad in Spain.

Family vacations were the worst.

Victoria always got her own hotel room.

I slept on pullout couches in hallways. Once, even in a closet that the resort marketed as a “cozy nook.”

In every family photo, Victoria stood center frame, glowing.

I was always at the edge, sometimes partially cut off—as if I’d wandered into the shot by mistake.

When I finally asked Mom about it, I was seventeen, desperate for an explanation.

She sighed.

“Sweetheart,” she said, “you’re imagining things. We love you both the same.”

But actions don’t lie.

A few months before the college decision, I found Mom’s phone unlocked on the kitchen counter. A text thread with Aunt Linda was open.

I shouldn’t have read it.

I did.

Poor Francis, Mom had written. But Harold’s right. She doesn’t stand out. We have to be practical.

I put the phone down and walked away.

That night, I made a decision I told no one about.

Not because I wanted revenge.

Because I wanted to prove something—to myself.

I opened my laptop—the cracked one with the dying battery—and typed into the search bar:

full scholarships for independent students

The results loaded slowly, and I stared at them like they were a door I didn’t know I was allowed to open.

At two in the morning, sitting on my bedroom floor with a notebook and a calculator, I did the math.

Eastbrook State: $25,000 per year.

Four years: $100,000.

Parents’ contribution: $0.

My savings from summer jobs: $2,300.

The gap was staggering.

If I couldn’t close it, I had three options:

Drop out before I even started.

Take on six figures of debt that would follow me for decades.

Go part-time, stretching a four-year degree into seven or eight years while working full-time.

Every path led to the same place: becoming exactly what my father had decided I was.

The twin who didn’t make it.

I could already hear the conversations at Thanksgiving.

“Victoria is doing so well at Whitmore.”

“And Francis… oh, she’s still figuring things out.”

But this wasn’t only about proving them wrong.

It was about proving myself right.

I scrolled through scholarship databases until my eyes burned.

Most required recommendations, essays, proof of financial need.

Some were scams.

Others had deadlines that had already passed.

Then I found something.

Eastbrook had a merit scholarship program for first-generation and independent students: full tuition coverage plus a living stipend.

The catch?

Only five students per year were selected.

The competition was brutal.

I saved the link.

Then I kept scrolling—and that’s when I first saw the name that would eventually change my life.

The Whitfield Scholarship.

Full ride.

$10,000 annually for living expenses.

Awarded to only twenty students nationwide.

I laughed out loud.

Twenty students in the entire country.

What chance did I have?

But I bookmarked it anyway.

I had two choices:

Accept the life my parents designed for me,

or design my own.

I chose the second.

But to do that, I needed a plan—and I needed it immediately.

That summer, I filled an entire notebook.

Every page was a calculation.

Every margin was covered in plans.

Job number one: barista at the Morning Grind, a campus café.

Shift: 5:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m.

Estimated monthly income: $800.

Job number two: cleaning crew for the residence halls.

Weekends only: $400 a month.

Job number three: teaching assistant for the economics department—if I could land it.

Another $300.

Total: $1,500 per month, roughly $18,000 a year.

Still $7,000 short of tuition.

That gap would have to come from scholarships—merit-based ones.

The kind you earn.

Not the kind you’re handed.

I found the cheapest housing option within walking distance of campus: a tiny room in a house shared with four other students.

$300 a month, utilities included.

No parking.

No AC.

No privacy.

It would have to do.

My schedule crystallized into something brutal but precise.

5:00 a.m.: work at the café.

9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.: classes.

6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m.: study, work, or TA duties.

11:00 p.m. to 4:00 a.m.: sleep.

Four to five hours a night.

For four years.

The week before I left for college, Victoria posted photos from her Cancún trip with friends—sunset beaches, margaritas, laughter.

I was packing my thrift-store comforter into a secondhand suitcase.

Our lives were already diverging.

And we hadn’t even started yet.

Every night before sleep, I whispered the same thing to myself.

This is the price of freedom.

Freedom from their expectations.

Freedom from their judgment.

Freedom from needing their approval.

I didn’t know then how right I’d be.

And I didn’t know that somewhere on the Eastbrook campus there was a professor who would see something in me that my own parents never could.

Freshman year—Thanksgiving.

I sat alone in my tiny rented room, phone pressed to my ear, listening to the sounds of home: laughter in the background, the clink of dishes, the warm chaos of a family gathering I wasn’t part of.

“Hello, Francis.”

Mom’s voice was distant, distracted.

“Hi, Mom. Happy Thanksgiving.”

“Oh. Yes. Happy Thanksgiving, honey. How are you?”

“I’m okay. Is Dad there? Can I talk to him?”

A pause.

Then I heard his voice in the background—muffled, but clear.

“Tell her I’m busy.”

The words landed like stones.

Mom’s voice returned, artificially bright.

“Your father’s just in the middle of something. Victoria was telling the funniest story.”

“It’s fine,” I said. “Are you eating enough? Do you need anything?”

I looked around my room: the instant ramen on my desk, the secondhand blanket, the textbook I’d borrowed from the library because I couldn’t afford to buy it.

“No, Mom. I don’t need anything.”

“Okay. Well, we love you.”

“Love you too.”

I hung up.

Then I opened Facebook.

The first thing in my feed was a photo Victoria had just posted: Mom, Dad, and Victoria at the dining table.

Candles lit.

Turkey gleaming.

Caption: Thankful for my amazing family.

I zoomed in.

Three place settings.

Three chairs.

Not four.

They hadn’t even set a place for me.

I stared at that image for a long time.

Something shifted inside me that night.

The ache I’d carried for years—the longing for their approval, their attention, their love—it didn’t disappear.

But it changed.

It hollowed out.

And where the pain used to be, there was only quiet emptiness.

Strangely, that emptiness gave me something the pain never had.

Clarity.

Second semester, freshman year: Microeconomics 101.

Dr. Margaret Smith was legendary at Eastbrook.

Thirty years of teaching.

Published in every major journal.

A terrifying reputation.

Students whispered that she hadn’t given an A in five years.

I sat in the third row, took meticulous notes, and turned in my first essay expecting a B-minus at best.

The paper came back with two letters at the top:

A+

Beneath the grade, a note in red ink:

See me after class.

My heart dropped.

What did I do wrong?

After the lecture, I approached her desk.

Dr. Smith was already packing her bag—silver hair pulled back in a severe bun, reading glasses perched on her nose.

“Francis Townsend,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Sit down.”

I sat.

She looked at me over her glasses.

“This essay is one of the best pieces of undergraduate writing I’ve seen in twenty years,” she said. “Where did you study before this?”

“Nowhere special. Public high school. Nothing advanced.”

“And your family? Academics?”

I hesitated.

“My family doesn’t support my education,” I said. “Financially or otherwise.”

The words came out before I could stop them.

Dr. Smith set down her pen.

“Tell me more.”

So I did.

For the first time, I told someone the whole story: the favoritism, the rejection, the three jobs, the four hours of sleep—everything.

When I finished, she was quiet for a long moment.

Then she said something that changed my trajectory forever.

“Have you heard of the Whitfield Scholarship?”

I nodded slowly.

“I’ve seen it,” I said. “But it’s impossible. Twenty students nationwide.”

“It’s rare,” she said, “not impossible. Full ride, a living stipend. And the recipients at partner schools give the commencement address at graduation.”

She leaned forward.

“Francis,” she said, “you have potential—extraordinary potential. But potential means nothing if no one sees it.”

She paused.

“Let me help you be seen.”

The next two years blurred into a relentless rhythm.

Wake at four.

Coffee shop by five.

Classes by nine.

Library until midnight.

Sleep.

Repeat.

I missed every party, every football game, every late-night pizza run.

While other students built memories, I built a GPA.

4.0—six semesters straight.

There were moments I almost broke.

Once, I fainted during a shift at the café.

“Exhaustion,” the doctor said. “Dehydration.”

I was back at work the next day.

Another time, I sat in my car—Rebecca’s car, actually. She’d lent it to me for a job interview—and cried for twenty minutes.

Not because anything specific had happened.

Just because everything had happened all at once for years.

But I kept going.

Junior year, Dr. Smith called me into her office.

“I’m nominating you for the Whitfield,” she said.

I stared at her.

“You’re serious?”

“Ten essays,” she said. “Three rounds of interviews. It’ll be the hardest thing you’ve ever done.”

She paused.

“But you’ve already survived harder.”

Part II — The Scholarship That Changed Everything

The application consumed three months of my life.

Essays about resilience.

Leadership.

Vision.

Phone interviews with panels of professors.

Background checks.

Reference letters.

Somewhere in the middle of it, Victoria texted me—for the first time in months.

Mom says you don’t come home for Christmas anymore. That’s kind of sad, TBH.

I read the message.

Then I put my phone face down and went back to my essay.

The truth was simple: I couldn’t afford a plane ticket.

But even if I could, I wasn’t sure I wanted to go.

That Christmas, I sat alone in my rented room with a cup of instant noodles and a tiny paper Christmas tree Rebecca had made me.

No family.

No presents.

No drama.

It was, somehow, the most peaceful holiday I’d ever had.

The email arrived at 6:47 a.m. on a Tuesday in September of senior year.

Subject: Whitfield Foundation — Final Round Notification

My hands were shaking so badly I could barely scroll.

Dear Miss Townsend, congratulations. Out of 200 applicants, you have been selected as one of 50 finalists for the Whitfield Scholarship. The final round will consist of an in-person interview at our New York headquarters.

Fifty finalists.

Twenty winners.

A forty percent chance—if all things were equal.

But things were never equal.

The interview was scheduled for a Friday in New York—eight hundred miles away.

I checked my bank account.

$847.

A last-minute flight would cost at least $400.

A hotel would eat the rest.

And rent was due in two weeks.

I was about to close my laptop when Rebecca knocked on my door.

“Frankie,” she said, “you look like you saw a ghost.”

I showed her the email.

She screamed.

Literally screamed.

“You’re going,” she said. “End of discussion.”

“Beck, I can’t afford it.”

“Bus ticket,” she said. “Fifty-three dollars. Leaves Thursday night. Arrives Friday morning. I’ll lend you the money.”

“I can’t ask you to—”

“You’re not asking. I’m telling.”

She grabbed my shoulders.

“Frankie,” she said, “this is your shot. You don’t get another one.”

So I took the bus.

Eight hours overnight.

Arriving in Manhattan at five in the morning with a stiff neck and a borrowed blazer from a thrift store.

The interview waiting room was full of polished candidates—designer bags, parents hovering nearby, easy confidence.

I looked down at my secondhand outfit, my scuffed shoes.

I don’t belong here, I thought.

Then I remembered Dr. Smith’s words.

You don’t need to belong.

You need to show them you deserve to.

Two weeks after the interview, I was walking to my morning shift when my phone buzzed.

Subject: Whitfield Scholarship — Decision

I stopped in the middle of the sidewalk.

A cyclist swerved around me, cursing.

I didn’t hear him.

I opened the email.

Dear Ms. Townsend, we are pleased to inform you that you have been selected as a Whitfield Scholar for the class of 2025.

I read it three times.

Then a fourth.

Then I sat down on the curb and cried—not quiet tears.

The kind of crying that makes strangers stare.

Three years of exhaustion, loneliness, and grinding determination poured out of me right there on the sidewalk outside the Morning Grind.

I was a Whitfield Scholar.

Full tuition.

$10,000 a year for living expenses.

And the right to transfer to any partner university in their network.

That night, Dr. Smith called me personally.

“Francis,” she said, “I just got the notification. I’m so proud of you.”

“Thank you,” I whispered. “For everything.”

“There’s something else,” she said.

“The Whitfield allows you to transfer to a partner school for your final year.”

I waited.

“Whitmore University is on the list,” she said.

Whitmore.

Victoria’s school.

“If you transfer,” Dr. Smith continued, “you’d graduate with their top honors, and the Whitfield Scholar delivers the commencement speech.”

My breath caught.

“Francis,” she said, “you’d be valedictorian.”

I thought about my parents—about them sitting in the audience for Victoria’s big day, completely unaware I was there.

“I’m not doing this for revenge,” I said quietly.

“I know,” she said.

“I’m doing it because Whitmore has the better program for my career.”

“I know that too,” she said.

A pause.

“But if they happen to see you shine,” she added gently, “that’s just a bonus.”

I made my decision that night.

And I told no one in my family.

Three weeks into my final semester at Whitmore, it happened.

I was in the library—third floor, tucked into a corner carrel with my constitutional law textbook—when I heard a voice that made my stomach drop.

“Oh my God,” Victoria said.

“Francis.”

I looked up.

She stood three feet away, a half-empty iced latte in her hand, mouth hanging open.

“What are you—how are you—” She couldn’t form a complete sentence.

I closed my book calmly.

“Hi, Victoria.”

“You go here since when?” she demanded. “Mom and Dad didn’t say—”

“Mom and Dad don’t know,” I said.

She blinked.

“What do you mean they don’t know?”

“Exactly what I said.”

Victoria set her coffee down, still staring at me like I’d materialized from thin air.

“But how? They’re not paying for— I mean, how did you—”

“I paid for it myself,” I said. “Scholarship. I transferred.”

The word hung between us.

Victoria’s expression shifted—confusion, disbelief, and something else.

Something that looked almost like shame.

“Why didn’t you tell anyone?” she asked.

I looked at her.

My twin sister.

The one who’d gotten everything I’d been denied.

The one who’d never asked—not once in four years—how I was surviving.

“Did you ever ask?” I said.

Her mouth opened.

Closed.

I gathered my books.

“I need to get to class.”

“Francis, wait.”

She grabbed my arm.

“Do you hate us?” she asked. “The family?”

I looked at her hand on my sleeve, then at her face.

“No,” I said quietly. “You can’t hate people you’ve stopped building your life around.”

I pulled my arm free and walked away.

That night, my phone lit up with missed calls.

Mom.

Dad.

Victoria again.

I silenced them all.

Whatever was coming, it would happen on my terms.

Victoria called them immediately.

I know because she told me later.

“She’s here,” Victoria said as soon as she walked through the door of her apartment. “Francis is at Whitmore. She’s been here since September.”

According to Victoria, the silence on the other end lasted a full ten seconds.

Then Dad’s voice.

“That’s impossible,” he said. “She doesn’t have the money.”

“She said scholarship.”

“What scholarship?” Dad snapped. “She’s not scholarship material.”

“Dad, I saw her in the library. She’s—”

“I’ll handle this,” he cut in.

Dad called me the next morning.

The first time he dialed my number in three years.

“Francis,” he said, “we need to talk.”

“About what?”

“Victoria says you’re at Whitmore. You transferred without telling us.”

“I didn’t think you’d care,” I said.

A pause.

“Of course I care,” he said. “You’re my daughter.”

“Am I?”

The word came out flat.

Not bitter.

Just factual.

“You told me I wasn’t worth investing in,” I said. “Remember that?”

Silence.

“Francis, I— that was four years ago.”

“In the living room,” I said. “You said I wasn’t special. You said there was no return on investment with me.”

“I don’t remember saying—”

“I do.”

More silence.

Then:

“We should discuss this in person at graduation,” he said. “We’re coming for Victoria’s ceremony, and… I know you’ll be there.”

“I’ll see you there,” I said.

And I hung up.

He didn’t call back.

That night, I sat in my small apartment—the one I’d paid for myself with money I’d earned—and thought about that conversation.

He didn’t remember.

Or he chose not to.

Either way, he’d never actually seen me.

Not really.

But in three months, he would.

And when that moment came, it wouldn’t be because I forced him to look.

It would be because he couldn’t look away.

The weeks before graduation became a strange kind of quiet.

I knew they were coming.

Mom.

Dad.

Victoria.

The whole perfect family unit descending on campus to celebrate Victoria’s achievement.

They’d booked a hotel.

Planned a dinner.

Ordered flowers for her.

They still didn’t know the full picture.

Victoria had told them I was at Whitmore.

But she didn’t know about the Whitfield.

She didn’t know about the valedictorian honor.

She didn’t know I’d been asked to deliver the commencement address.

Dr. Smith called to check in.

She’d made the trip to watch.

“Do you want me to notify your family about the speech?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “I want them to hear it when everyone else does.”

She was quiet for a moment.

“This isn’t about making them feel bad,” she said.

“No,” I said honestly. “It’s about telling my truth. If they happen to be in the audience, that’s their choice.”

Rebecca drove up for the ceremony.

She helped me pick out a dress—the first new piece of clothing I’d bought in two years that wasn’t from a thrift store.

Navy blue.

Simple.

Elegant.

“You look like a CEO,” she said.

“I feel like I’m going to throw up,” I said.

“Same thing, probably,” she said.

The night before graduation, I couldn’t sleep.

Not from nerves—not exactly.

I kept wondering what I would feel when I saw them.

Would the old pain come rushing back?

Would I want them to hurt the way I’d hurt?

I stared at the ceiling until three in the morning searching for an answer.

What I found surprised me.

I didn’t want revenge.

I didn’t want them to suffer.

I just wanted to be free.

And tomorrow—one way or another—I would be.

Part III — The Name They Didn’t Expect

Graduation morning: May 17.

Bright sun.

Perfect blue sky.

The kind of weather that felt almost ironic.

Whitmore’s stadium seated three thousand.

By nine a.m., it was nearly full—families pouring through the gates, flowers and balloons everywhere, the hum of excited conversation rising and falling like waves.

I arrived early, slipping in through the faculty entrance.

My regalia was different from the other graduates.

Standard black gown, yes.

But across my shoulders lay the gold sash of valedictorian.